Interview-conversation with Diego Giménez

Edition by Fabrizio Boscaglia.

The Pessoa researcher Diego Giménez, from the University of Coimbra, talks to another Pessoa researcher, Fabrizio Boscaglia from Lusófona University, about Fernando Pessoa and digital technologies. The starting point is the academic-informatics project and portal LdoD Archive, a digital and plural edition of Fernando Pessoa’s Livro do Desasossego, on which Diego Giménez collaborated in the context of the University of Coimbra. Fabrizio Boscaglia’s questions and reflections are in bold, while the answers are from Diego Giménez.

Happy reading!

1. Why and how did the LdoD Archive come about?

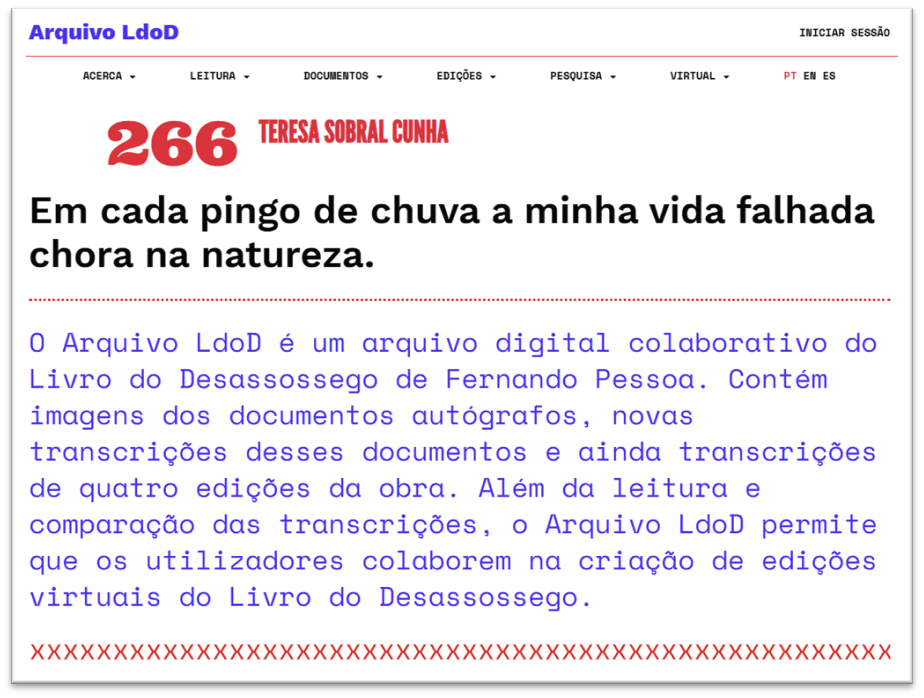

The head of the Arquivo LdoD is Professor Manuel Portela, from the University of Coimbra, who specialises in English Literature, Portuguese Literature and Digital Humanities. The idea for the archive originally occurred to him around 2009: he wanted to explore all the potential of the Livro do Desassossego in a digital context, in other words, within the Digital Humanities, and at the same time, the potential of the Digital Humanities to represent and study Pessoa’s work. We started in 2012, and the Arquivo LdoD was presented to the public in 2017.

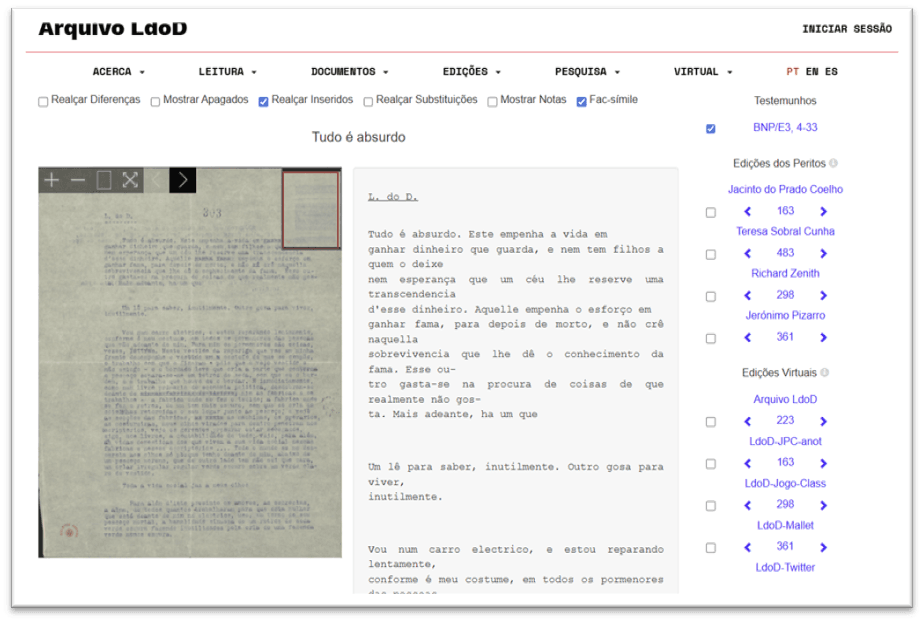

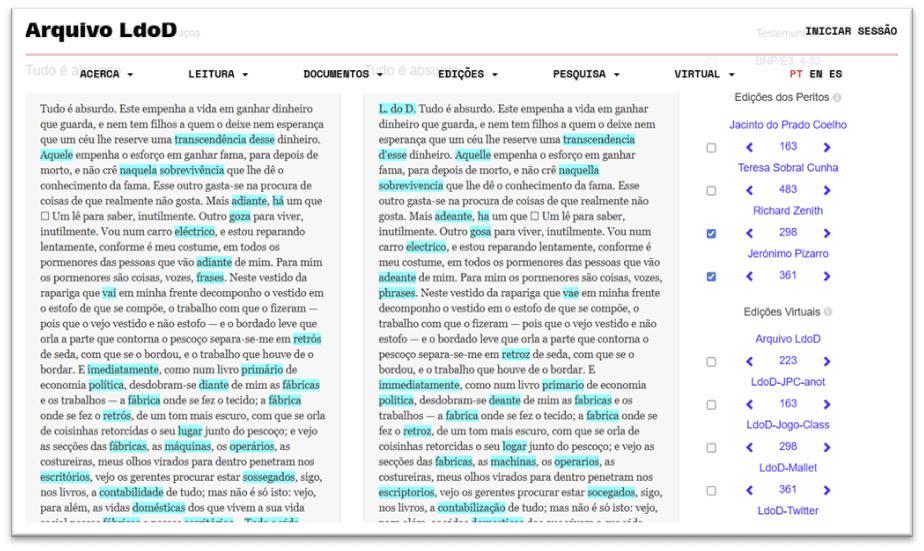

Since there are several paper editions of the Livro do Desassossego, what the LdoD Archive showed was that it didn’t make much sense to canonize one edition above the others, because there isn’t one Livro do Desassossego, there are many ‘Livros do Desassossego ’, as many as there are editors, or rather readers who dive into the fragments and manage to put together, so to speak, their own edition, or their own idea of the Livro. The Arquivo LdoD, among other features, allows everyone to construct their own edition of the work, in terms of the order of the texts and the choice of transcriptions. The Arquivo LdoD therefore valorizes the textual fragmentation of Desassossego, now represented in a multiple and comparative way between the originals and the different editions.

In the Arquivo LdoD we have made available and comparable the editions by Jacinto do Prado Coelho, Teresa Sobral Cunha and Maria Aliete Galhoz (1982), Teresa Sobral Cunha (1990), Richard Zenith (1998) and Jerónimo Pizarro (2010). It can be said that over the decades these have been considered the most recognised and important early editions. In addition, what makes the various editions of the Livro even more interesting is that the editors gave life to an intense critical debate between themselves, even in the introductions, each to defend their own editing choices. Working with the archive has shown that every edition responds to the reading and subjectivisation of the unfinished work.

2. What was Diego’s role and what kind of work was it?

I started working on the Arquivo LdoD coding the extracts, i.e. applying computer code to the texts, around 2012. All this was done using a computer coding language (Text Encoding Initiative, or T.E.I.), starting from Pessoa’s original text. Coding involves adding code to an original text so that it can be processed and represented by software. Through coding, what could be understood as digital philology was carried out, digitally representing all the textual variants that the original documents and the comparison with the editions presented. For example, the spelling variants were marked: in the original text, Pessoa wrote ‘attenção’, following the pre-1911 spelling. Some of the editors modernised it to ‘atenção’ and others kept the old spelling. We have therefore coded all these variants, among others, with computer code. Given the volume of the corpus, you can imagine the work involved.

On the website, we can also see each of Pessoa’s original documents in facsimile, whether handwritten or typewritten, as well as the resulting coding, where we can check for any changes or additions made by Pessoa himself.

What coding allowed us to do was not only to see what Pessoa wrote, but also to map and analyse other meta-textual data, for example, the type of paper, the type of sheet, the type of ink. All this information became a computer-coded description. There were fragments that took two or three days to code, because there were so many textual differences between editions, with pages and pages of code.

3. It seems almost fatal, when we talk about Pessoa, to open a box from which material keeps coming out… Unpublished, heteronyms, editions… Each editor is, in fact, almost another heteronym, because each of us, when we read Pessoa, has our own epiphanies and builds our own Pessoa. In your personal experience as a reader, editor and scholar of the Book, what sparked this project in you?

It was very important for me to start codifying the fragments, which meant reading the materials in Pessoa’s estate document by document, comparing them with the different editions published. My previous training had been in philosophy, so my tendency when working on the Livro do Desassossego was always, to use Gumbrecht’s expression, to look for the production of meaning in the work, to look for the great concepts of truth, of reality… I was always a little lost in the great concepts of philosophy. My approach to literature from philosophy came from the feeling that there is a truth in the work of art that escapes reason or merely speculative thought.

This was the feeling of epiphany I had when I read and reread Livro do Desassossego: ‘this is very beautiful, but I don’t know why’. Jorge Luis Borges spoke much more elegantly about this, because he always suspected that meaning is something we add to the poem, that we start from a void, from a sensation of beauty, and then look for meaning. Working with the code has therefore been this search for meaning, but one that has no answer. This has helped me to read and compare the text exactly for what it is, paragraph by paragraph, line by line. This kind of close reading has served as a basis for further speculation.

4. There are passages in the Livro do Desassossego , like Álvaro de Campos’ futuristic verses, in which Pessoa represents, interprets and, as it were, ‘sings’ the advance of science and technology, which at that time was given a decisive boost – just as it is today, unfortunately – by the war dynamics of 1914-1918. How does Diego read Fernando Pessoa in the context of the age of technology and, vice versa, how does he read our technological age in the light of Pessoa’s work? Without forgetting that Pessoa, through heteronymism, is perhaps also anticipating, in some way, the era of avatars and fictitious profiles on social networks…

I agree, modernist literature does anticipate contemporary writing practices. In this regard, there is a doctoral thesis by Maria dos Prazeres Gomes, Outrora Agora: Relações Dialógicas na Poesia Portuguesa de Invenção, which argues that modern writing practices contain or prefigure contemporary writing practices. This happens above all because of the combinatory aspect, because these practices consider language as a set of elements that combine with each other – which is even at the basis of a certain idea of computation.

As for Pessoa as the forerunner of ‘multiple digital identities’, a little jokingly we can think of the heteronyms as avatars, yes, on the web itself there are texts and images in which Pessoa is seen as the true and first creator of ‘fake profiles’. A writer like Fernando Pessoa, among others, undoubtedly helps us to think about many issues in the current technological age.

Already in Pessoa’s time, his Lisbon is like Baudelaire’s Paris, as it was studied by Walter Benjamin in that emergence of 19th century modernity, talking about steel, the invention of the daguerreotype and the flâneur. There are some elements or marks of modernity that are very present in Pessoa’s work: the tram, the cinema, the telephone, the typewriter, the train, the car, etc. Take that passage from The Book of Disquiet, in which the narrator Bernardo Soares is on the tram and looks at a girl’s dress, and begins to think about the whole system of producing that fabric. From that visual sensation, he goes on to intellectualise it, thinking about the whole system of industrial production, so typical of the capitalist system. He already describes that whole process very well, from the factory to the girl’s body, in the time of a tram journey that could have been five or seven minutes, the narrator claims to have lived his whole life. In this brief interval of time, he reconstructs an entire production system. It’s a fantastic fragment.

5. Pessoa almost seems to be trying to spiritualise technology, trying to extract and at the same time construct that which something apparently cold and mechanical is spiritual and therefore free, in a poetic way. There’s a poetic ontology of technology here that constitutes a great and fascinating challenge from a philosophical point of view. Regarding the danger of humanity losing touch with Being because of the ‘age of technology’, Heidegger said in 1959 that ‘only a God can save us’ from this dehumanization. And he said it rationally, philosophically, not from a religious point of view. At the same time, Heidegger himself argues that it is the poet, rather than the philosopher, who finds and pronounces Being. Is Pessoa doing this, in other words, finding Being in the ‘age of technology’, as if it were through him that divinity acts that ‘can only save us’? Or is Pessoa, on the contrary, mythologising technology, contributing to this dehumanization?

Pessoa undoubtedly poeticises modern life, but not in the sense of a dehumanising mythification of technology. His vision and his writing are always based on an aesthetic-literary sense. The poetic dimension does bring poeticisation closer to technique. In this sense, I agree with this possible ‘Heideggerian’ reading of Pessoa.

6. Let’s continue ‘playing for real’: would Fernando Pessoa like the web and so-called ‘Artificial Intelligence’?

I think he would find Artificial Intelligence very funny, and he could use it as a means to create. He could type very well, directly, with a good rhythm. For example, Heidegger himself was very critical of the typewriter, arguing that with it all men are equal, because handwriting disappears, and in handwriting there is something of the soul that is transmitted. That’s why the German philosopher criticised the typewriter. But in a different way, when I read Pessoa’s typewritten texts, I see soul there. In fact, I think technology can be valuable if it is used as a means to create. Not if it’s conceived as a divinity or as the answer to everything.

7. There are artists who are producing literary writing through so-called ‘Artificial Intelligence’. Regarding this act of delegating-giving on the part of the artist, we can ask: where is art itself going?

In this respect, consider Mark Amerika’s book, My Life as an Artificial Creative Intelligence, a kind of autobiography without facts produced by Artificial Intelligence. As part of the Pessoa 3.0 project, we organised some seminars on Pessoa and the digital context which led to a special issue of the magazine Texto Digital, where Mark Amerika published a text inspired by Pessoa, showing experiments carried out with Artificial Intelligence. Another academic who has published in this area is Rui Torres, from Fernando Pessoa University. He works on combinatorial electronic literature. For example, in ‘Um Corvo Nunca Mais’, he uses computing to create poems from Poe texts translated by Pessoa. Recently, in his text «Combinatória, Geração Textual e as Novas Fronteiras da Literatura Computacional», he compared combinatorial electronic literature with the generative technology of Artificial Intelligence.

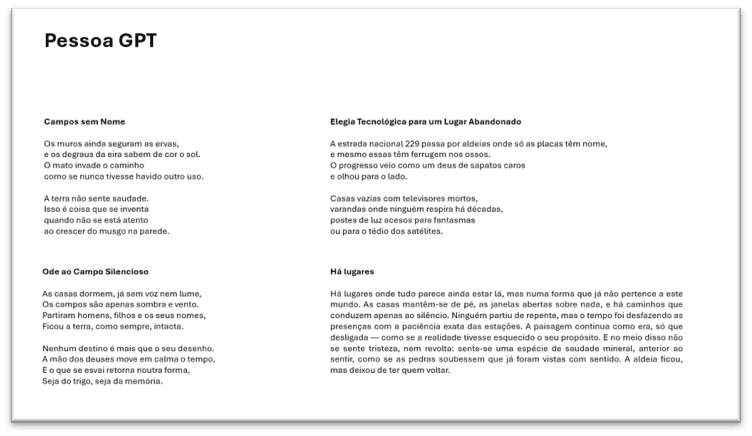

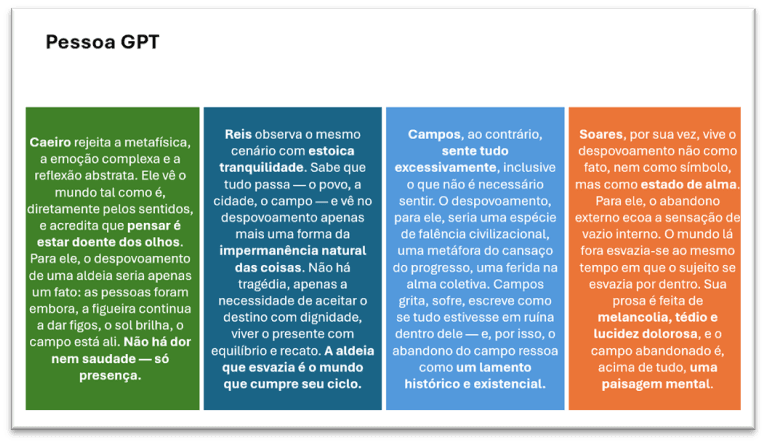

I’ve done some ‘playful’ experiments in this regard myself. I gave Chat GPT some poems by the orthonymous Pessoa, the three main heteronyms, and prose by Bernardo Soares. So I asked Chat GPT to create new poems and prose, imitating Pessoa and his fictional authors, with the theme of the texts being ‘the depopulation of the interior in Portugal’. I challenge our readers to work out which of these Pessoa authors each of the following texts corresponds to:

Afterwards, I asked Chat CPT to describe the essential characteristic of each of these Pessoa authors, particularly in relation to the chosen theme. Here’s the result:

8. All of this is surprising, but also worrying. In fact, this type of writing is also fuelling a phenomenon of manipulation and mystification of writing, as can be seen, for example, in school and university contexts, where there are students who use so-called ‘Artificial Intelligence’ to produce work for assessment, thus deceiving teachers. Not to mention the fact that human beings can become or seem obsolete in the face of the possibility of an increasingly ‘individualised’ ‘Artificial Intelligence’. How does Diego view these challenges?

The humanities in academia can be very critical about Artificial Intelligence, as if it were an aberration for creation and thought. But the fact is that students are going to use it. That’s why I think it’s necessary to create a critical mass in universities so that digital representation can be approached critically – either in favour of it or against it. Otherwise, the preservation of literary heritage in a digital context will be done a disservice. To put it very clearly and succinctly: are we going to let machines produced by great technological powers, oblivious to the specificities of the Portuguese language, define what Fernando Pessoa and other authors of Portuguese literature are?

It’s frightening what could happen. I also think that there is a lot of marketing work associated with the term ‘Artificial Intelligence’: it’s not about intelligence; it’s about large language models, computer algorithms, which are not intelligent, at least according to what we think of as human intelligence. What they do is generate texts based on statistics, based on millions of readings of texts they are able to statistically calculate which words or concepts are associated with each other. Statistically, this does not mean that there is a necessary link between elements.

Another problem is: what texts are these Artificial Intelligences feeding on to create these statistics? I’ll give you an example: let’s imagine that, in a playful game like the one I’ve illustrated, the texts about Pessoa that the Artificial Intelligence is going to look for are mainly studies indexed in North American journals, not including, for example, studies by great Portuguese Pessoa writers such as Eduardo Lourenço or Jacinto do Prado Coelho, among others. The answer the machine will give will be very partial, reflecting only certain interpretative lines. And here, I repeat, we must take a critical approach and create critical mass in the faculties, we cannot allow the digital representation of Fernando Pessoa to be totally distorted.

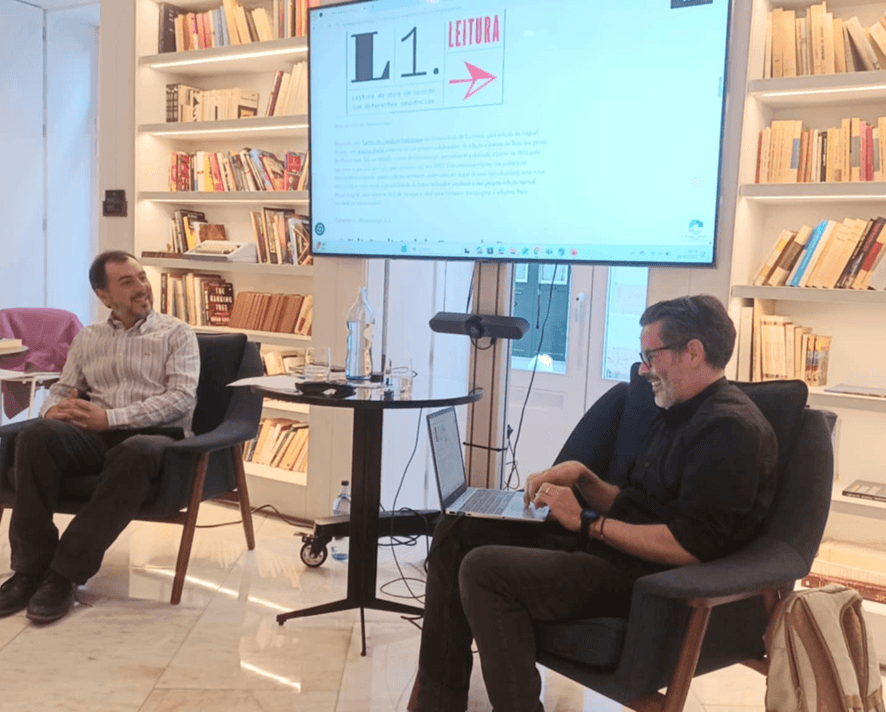

Thanks to Nuno Ribeiro, Emília Cerqueira, Noémia Simões and all the participants in the Desassossego Digital event (Lisboa Pessoa Hotel, 24 July ’25), for helping to fuel the debate that resulted in some of the topics discussed in this interview.

Read more:

> 5 (+1) sites to read and admire the work of Fernando Pessoa

> Literary tourism in Portugal (I): 5 itineraries and digital resources

Fabrizio Boscaglia

_

Discover Lisboa & Pessoa, from Lisboa Pessoa Hotel, a themed boutique hotel inspired by Fernando Pessoa.